The Bagisu Culture

Uganda’s most fearsome patriarchal tribe and their culturally unique circumcision ceremony. Guardians of Mount Elgon, Uganda's Arabica coffee capital and Uganda's only bullfighting sport.

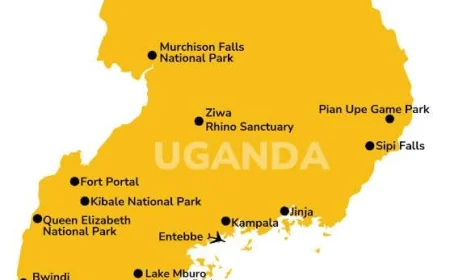

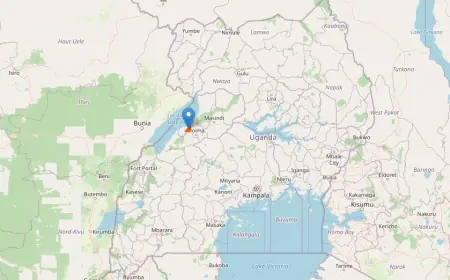

Mount Elgon's western and southern halves are home to the Bagishu. The mountain spreads out like the fingers of a hand to the west, with steep and narrow valleys in between. The southern land is strewn with hills jammed against a high escarpment like a crumpled tablecloth. The escarpment gradually gives way to a plain to the northeast, where Iteso lives.

Quick facts

- Lugisu/Lumasaba is the language spoken by the Bagisu.

- The Bagisu are the guardians and custodians of Uganda's side of Mount Elgon, also called Mount Masaba.

- The Bagisu are the guardians of Uganda's Arabica coffee capital, which is mainly grown on the slopes of Mount Elgon.

- The Bagisu are the guardians and custodians of Sisiyi Falls located in Bulambuli (Bugisu region), which are magnificent and offer great views and hiking experiences.

- The Bagisu are the guardians and custodians of Uganda's first and only bullfighting sport.

- The Bagisu are the 7th largest tribe in Uganda, constituting 5% of Uganda's population.

Origins of the Bagisu

There is no tradition of an early migration among the Bagishu. They claim that their forefathers were Mundu and Sera, who, according to legend, emerged from a hole on Mt. Masaba (Elgon). Their early years appear to have been antisocial, almost based on the "survival of the fittest" principle. Little is known about their history, but they are known to be related to the Bukusu, a sub-group of the Kenyan Luhya. The Bagishu and the Bukusu are thought to have split up in the nineteenth century. It is no longer fashionable to claim that they have always lived where they are since historical times. The first Bugisu immigrants are thought to have arrived in the Mt. Elgon area in the 16th century.

The political set-up of Bagisu

Clans formed a loose political structure among the Bagishu. We Sikuka had an elder known as Umwami in each clan (chief of the clan). These men were selected based on their age and wealth. They were in charge of maintaining law and order as well as the clan's unity and continuity. They were also in charge of upholding and maintaining the clan's cultural values, as well as offering sacrifices to the ancestral spirits. Stronger chiefs would frequently extend their influence to other clans, but no chief was ever able to unite all of them into a single political entity. The rainmakers and sorcerers were also important figures in Bugisu.

The traditional faith of Bagisu

The Bagishu have a strong belief in the power of magic. Their perspective on even the most mundane events was tinged with magic. Bugisu's magic experts were divided into three categories. The witch doctor proper, or the sorcerer known as umulosi, is next to the scale; the witchfinder is known as omufumu; and the least harmful is the medicine man. The medicine man's job was to determine when sacrifices should be made. He also sold anti-witchcraft medicine, snake bites, charms for use in battle, and infection-inducing drugs. He could both read an oracle and keep a creditor away from collecting debts.

The Umufumu possessed the abilities of a medicine man, as well as the ability to detect who had cast a spell against someone. He lacked the ability to cast a spell, however. He could easily figure out who had done it, and steps would be taken to obtain an antidote. The Umulosi were the most feared and dangerous of all the tribes. He was a hereditary positionholder who lived alone in the woods. He wielded considerable power, and he occasionally combined the functions of witchfinder with his other responsibilities. He was thought to be a direct medium, and no medicine could counteract his spells.

There were several types of witchcraft, some of which were associated with men and others with women. Buyaza was the name of one of them. It was done by putting a snake's backbone into some of her victim's belongings and then summoning the spirits to attack him or her; other forms involved various actions and objects, but the end result was usually the same, causing harm or misfortune to the victim. Gamalogo, which was specific to women, and gamasala, which was specific to men, required the use of food scraps encased in a poisonous caterpillar cocoon and placed in the thatch of the victim's hut.There were several types of witchcraft, some of which were associated with men and others with women. Buyaza was the name of one of them. It was done by putting a snake's backbone into some of her victim's belongings and then summoning the spirits to attack him or her; other forms involved various actions and objects, but the end result was usually the same, causing harm or misfortune to the victim. Gamalogo, which was specific to women, and gamasala, which was specific to men, required the use of food scraps encased in a poisonous caterpillar cocoon and placed in the thatch of the victim's hut. To bewitch cattle, the men used a technique known as nabulungu. Men also used a method known as Mutabula, which entailed burying a small flat woven basket in the ground outside the intended victim's hut. These were only a few examples. There were a variety of other types and manifestations of witchcraft.

Judicial system

In their belief in witchcraft, the judicial system was muddled. Even if the accused is innocent, once named by a witch finder, he or she is forced to commit suicide. If a woman was suspected of an evil practice such as sorcery, her husband had no choice but to send her away, and custom demanded that his own people reject her as well. If the witch finder failed to remove the spell he cast on the victim, or if the victim had already died, the person named by the witch finder was usually killed.

The process of determining who cast the spell took an unusual turn. The accused was summoned and forced to confess after being confronted with the corpse or the sick man. If he refused, he would be subjected to a series of other ordeals. The use of a hit knife was the most common. He would be considered guilty of the crime if he was burned when a hot knife was placed on his body, but he would be considered innocent if he was not burned. However, it is said that there have been instances where some people have avoided being burned, and there have been living witnesses to this fact.

The circumcision ritual of Bagisu

In an event known as "Imbalu," the Bagisu circumcise their sons. This is a ceremony that marks the transition from boyhood to manhood. The Imbalu Festival is a well-attended event among Bagisu and Ugandans alike. This event takes place every "even" year, and every "odd" year. The Bagisu's most popular dance is the "Imbalu dance." The dance, which is also known as "Kadodi," is performed to the beat of Kadodi drums. A series of jumps, whistling, and dances make up the routine. Ine'mba, Infu'mbo, Inso'nja, Tsinyi'mba, and Kamabeka are some of the other dances.

Even among the Bagishu, the origins of this practice are shrouded in mystery. According to one legend, it began as a request from the Barwa (Kalenjin) when Masaba, the Bagishu hero ancestor, desired to marry a Kalenjin girl. According to another legend, the first person circumcised had a problem with his sexual organs, and the circumcision began as a surgical procedure to save the man's life. According to legend, the first person to be circumcised was punished for seducing other people's wives. According to legend, it was decided to circumcise him to castrate him. When he recovered, he resumed his previous practices, and word got out that he was quite good at them. Other men decide to circumcise as well in order to compete favorably.

The Bagishu have a strong sense of superstition. An initiate is given herbs called ityanyi before being circumcised. Its goal is to pique the candidate's interest in circumcision. Itenyi is frequently tied around the initiate's big toe or placed in a position where he might accidentally jump over it. If a candidate who has taken itenyi is delayed or prevented from being circumcised, it is believed that he will circumcise himself because his mind is so stimulated towards circumcision that nothing else can distract him.

Circumcision among the Bagishu occurs bi-annually during leap years. When a boy reaches puberty, he must perform the ritual. Those who flee are apprehended and circumcised with force and scorn. The initiates are prepared for circumcision by walking and dancing around villages for three days prior to the day of circumcision. Their relatives join them in dancing, and there is a lot of drumming and singing. The processions are enthusiastically attended by girls, particularly the initiates' sisters. When a boy is circumcised, it is thought that he becomes a true Mugishu and mature person. A Musani is a person who has not been circumcised.

The initiates are gathered in a semi-circle on the day of circumcision. Each initiate's operation is fairly quick. The circumciser and his assistant go from place to place, performing the ritual as needed. The assistant circumciser removes the foreskin from the penis, which the circumciser then cuts away. The circumciser goes even further, removing a layer from the penis that is thought to develop into a new top cover for the penis if not removed. The circumciser moves on to the lower part of the pennies and cuts off a muscle. The circumcision ritual comes to an end with these cuttings.

The initiate is made to sit on a stool after circumcision and then wrapped in a piece of cloth. After that, he is taken to his father's house and forced to walk around it before being allowed to enter. The initiate is not allowed to eat with his hands for three days. He has been fed. They claim it's because he hasn't completed his manhood rituals.

The circumciser is invited to undertake the ritual of washing the hands of the neophyte after three days. After this procedure, the initiate is allowed to eat with his hands. The initiate is declared a man on the same day. The tradition then permits him to marry. The initiate is taught the responsibilities and demands of manhood during the ceremony. He is also told that agriculture is very important and that he should always act like a man.

The healing of the cuts is thought to be dependent on the number of goats slaughtered during the circumcision. A ritual is done after the healing. All new initiates in the area are required to attend. Iremba is the name given to this rite. It is a significant ritual that is now attended by all village residents, including government officials. During the ceremony, the initiate might choose any girl and have sexual relations with her; the girl could not refuse. If a girl refuses, it is thought that she will never have children when she marries.

Circumcision used to be done in special enclosures where only the initiates and circumcisers were allowed. From the outside enclosure, the rest of the assembly would simply wait and listen. Today, though, everyone is welcome to observe the entire operation. The initiate's bravery is recognized by his or her firmness and valiant endurance.

The marriage ritual of Bagisu

Marriage was traditionally arranged by the boy's and girl's parents, frequently without the girl's knowledge or agreement. Following the agreement on the bride price, a delegation from the boy's side would arrive with the boy and offer the bride. A guy might marry as many wives as he wanted as long as he had the financial means to do so. In the event of a divorce, the girl's parents would receive all of the bridal wealth they had asked for. This was dependent on whether the woman had left right after marriage or had failed to have children. Only a portion of the bride fee would be reimbursed if she had children.

Birth and naming of Bagisu

The majority of births took place in the home. Traditionally, a medicine man would be consulted in order to prescribe drugs to alleviate labor pains. During the course of the labor, the husband may be necessary to assist the woman. The woman would cut the umbilical cord after giving birth and it would be buried.

The child's name was not given right away. It would generally wait until the youngster began to wail nonstop, say throughout the day or night. According to legend, an ancestor would then appear in the form of a dream and dictate the name for the child. The name that was demanded was usually that of an ancestor who appeared in the dream. No one was meant to challenge the propriety of the name suggested in this way.

The Death Ritual of Bagisu

People would cry aloud when someone died, and the body of the deceased would be kept in the house for three days before being buried. This was true for both men and women. On the fourth day, the body was laid to rest.

During the burial process, there were complex rites performed. If the deceased was barren, a hole was cut at the back of the home. It would be used to transport the body to its last resting place. In the instance of a parent, the body would be taken through the regular door. Women who died unmarried were treated as if they were barren, but such occurrences were uncommon because older girls were frequently pushed away from their households by their brothers to marry. Before the corpse was buried, it was prayed that no one present was responsible for its death, and that its spirit would not return because they had left no trace on earth and their names had never been given to anyone yet born.

There was enough food and brew to go around. Following the burial, a ceremony would be held. The elders were in attendance. If the deceased was the household's head, this ceremony would appoint an heir. The requirements for selecting an heir required that he or she be well-behaved and considerate. It didn't matter if the heir was a girl or a boy, or if he or she was younger than some of his or her senior siblings and sisters.

Economical structure of Bagisu

The Bagisu, like many Bantu groups, are farmers. Matooke (Kamtore), potatoes (kamapondi), millet, beans (kamakanda), and peas were among the principal crops used for survival. They also raise cattle, sheep, and goats in addition to agriculture.

Arabica coffee is grown at altitudes of up to 5000 feet above sea level, with the majority of it supplied to Bugisu Cooperative Union (BCU), while other coffee firms exist. Cotton, on the other hand, is grown on the lower plains, which can reach as low as 4000 feet above sea level. Tobacco is another profitable crop that a small percentage of the population cultivates.

Bananas (matooke) are farmed primarily for food, but they are also sold to complement the Bagisu's revenue from coffee, cotton, and tobacco. Maize, beans, millet, sorghum, yams, and cassava are also grown by the Bagisu. The Bagisu obtain millet and other consumables from the Itesots, Banyoli, Jopadhola, Bagwere, and Sabinys during unfavorable meteorological conditions, which they employ in the conduct of imbalu circumcision rituals.

The Bagisu do business with their neighbors as well. Food, sugar, salt, soap, animals, and musical instruments are among the things traded.

After drying, the millet and maize were placed in granaries, which are big wicker baskets with removable lids. The baskets were approximately five feet tall and three feet wide.

Villagers raised the stones off the ground with boulders or tree stumps and covered the exterior with cow manure to protect their crop from rain and insects.

Bagisu staple food

The Bagisu are a farming people. Among the crops they grow are bananas, maize, millet, sorghum, cassava, sweet potatoes, groundnuts, sim sim, vegetables, and coffee. "Kamaleya," dried bamboo shoots cultivated on Mount Elgon, are their staple diet, which they blend with groundnuts or sim sim. The Non-Bagisu name for Kamaleya is "Malewa," and it can be consumed as a food or used as a condiment with other foods.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

11

Like

11

Dislike

4

Dislike

4

Love

7

Love

7

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

2

Angry

2

Sad

1

Sad

1

Wow

3

Wow

3