The Baganda and their rich cultural heritage

A detailed insight into the rich traditions of the Buganda culture and beliefs

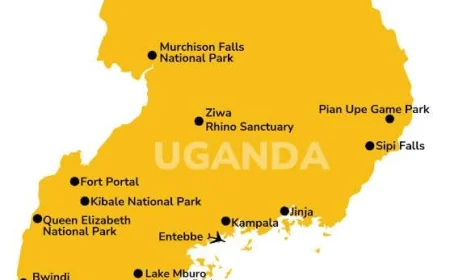

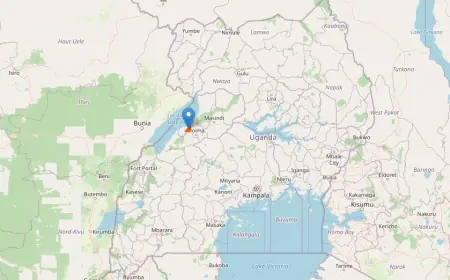

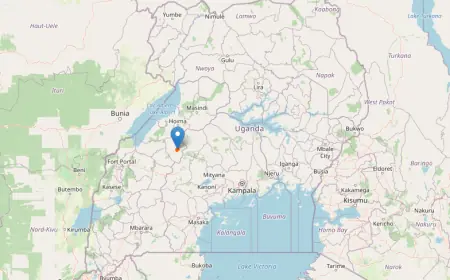

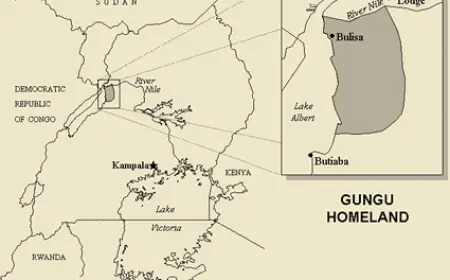

The Baganda are Uganda's most populous ethnic group, and the Kingdom of Buganda was the most powerful of the past kingdoms. It accounts for more than a quarter of Uganda's entire land area. Buganda is home to Kampala, Uganda's largest city and capital. They occupy Uganda's central region, historically known as the Buganda province. As a result, the Baganda can now be found in Kampala, Mpigi, Mukono, Masaka, Kalangala, Kiboga, Rakai, and Mubende.

FUN FACTS

PRONUNCIATION: bah-GAHN-dah

LOCATION: Uganda

LANGUAGE: Luganda

RELIGION: Christianity (Protestantism and Roman Catholicism); Islam

Baganda's Origins

The Baganda's early history is murky, with several competing legends about their beginnings. According to one account, they are descendants of Kintu, the legendary character from Baganda mythology who was the first human. He was claimed to have wedded Nambi, the creator deity Ggulu's daughter.According to another legend, Kintu According to another legend, Kintu is said to have arrived from the east, via Mount Elgon, and went through Busoga on his route to Buganda.

According to another legend, the Baganda are the ancestors of a people that arrived from the east or northeast around the year 1300. According to legends recorded by Sir Apolo Kagwa, Buganda's leading ethnographer, Kintu, the original Muganda, is claimed to have dropped to Earth at Podi, gone on to Kibiro, and finally founded Buganda at Kyadondo in Uganda's modern-day Wakiso District, according to legends recorded by Sir Apolo Kagwa.

Because the Baganda are Bantu, their origins are most likely in the region between West and Central Africa (around what is now Cameroon), and they came to their current position via the Bantu Migration.

The most widely accepted narrative of the origin of the Kingdom of the Baganda (Buganda) is that it was founded by Kato Kintu. This Kato Kintu differs from the mythical Kintu in that he is widely acknowledged as a historical figure who created Buganda and became its first 'Kabaka,' taking the name Kintu to prove his legitimacy as a monarch in relation to the mythology of Kintu. He was successful in bringing together a slew of warring tribes to build a powerful kingdom.

The language spoken by Baganda

Luganda is a Bantu language spoken by the Baganda. It belongs to the Niger-Congo language family. Muganda is the single form of Baganda in the Luganda language. Luganda, like many other African languages, is tonal, which means that some words are distinguished by pitch. Words with the same spelling but distinct pitches might have various meanings. Luganda is full of metaphors, proverbs, and legends.

Speech skills are taught to children in order to prepare them for adult life in a linguistically rich culture. In a game of ludikya, or "talking backward," a bright child can effectively engage his or her companions. omusajja ("man"), for example, becomes jja-sa-mu-o. In another variant of the game, the letter z is placed after each syllable that contains a vowel, followed by the vowel in that syllable. omusajja would become o-zo-mu-zu-sa-zajja-za in this rendition. Boys and girls both play ludikya, which they claim is commonly used to keep secrets from adults hidden.

Religion

The majority of Baganda today are Christians, with Catholics and Protestants roughly evenly split. Muslims make up about 15% of the population (followers of Islam).

The Balubaale cult was an indigenous (native) religion practiced by the majority of Baganda in the second half of the nineteenth century. In Buganda, there were three temples dedicated to Katonda (the major god), all of which were located in Kyaggwe and were overseen by priests from the Njovu tribe. Each of these gods (balubaale) was concerned with a different issue. There was a god of fertility, a god of combat, and a god of the lake, for example.

The other Balubaale served a unique purpose. Ggulu, god of the sky and father of Kiwanuka, god of lightning, was the most significant of them all. There was also Kawumpuli, the disease god, Ndaula, the smallpox god, Musisi, the earthquake god, Wamala, the god of Lake Wamala, and Mukasa, the god of Lake Victoria. Kitaka was the god of the ground, while Musoke was the god of the rainbow.

Throughout Buganda, there were temples dedicated to the many Balubaale. Each temple had a medium and a priest who operated as a liaison between the Balubaale and the people and had power over the temple. Priesthood was inherited in some clans, however a priest of the same god may be found in other clans.

The Kings had their own shrines where they could worship. The king's temple was taken over by Nnaalinya, the royal sister. The Balubaale religion was founded by Kabaka Nakibinge to reinforce his authority, according to Baganda legend, and he integrated both political and religious roles in the process.

Baganda today are deeply religious, regardless of their creed.

FOOD

Matooke, a plantain, is the Baganda's staple diet (a tropical fruit in the banana family). It's often served with groundnut (peanut) sauce or meat soups, and it's steamed or cooked. Eggs, fish, beans, groundnuts, cattle, poultry, and goats, as well as termites and grasshoppers in season, are also good sources of protein. Cabbage, beans, mushrooms, carrots, cassava, sweet potatoes, onions, and a variety of greens are also common veggies. Sweet bananas, pineapples, passion fruit, and papaya are some of the fruits available. Indigenous fermented beverages derived from bananas (mwenge), boiled pineapple juice (munanansi), and maize are among the beverages available (kasoli). Despite having cutlery, most Baganda prefer to eat with their hands, especially at home.

Marriage culture in Buganda

Jangu onfumbire was the customary term for marriage (come cook for me). Marriage was a very significant component of life for the Baganda. Normally, a woman is not valued unless she is married. A man would not be considered whole until he was married. And the more women a man had, the more he was considered a man. This implies that the Baganda were definitely polygamous. A guy might marry five or more wives as long as he could care for them.

Previously, parents would initiate and manage their children's marriage arrangements. For example, a father could choose a husband for his daughter without the daughter questioning whether the groom chosen was too old, too young, or undesirable. It was customary for elderly men to rekindle their love lives by marrying young women. However, as time passed, boys were able to make their own decisions and, with the assistance of their families, proceeded to make legal marriage preparations. The girl's only contribution would be her consent. A formal ceremony would be held after the proper introductions and payment of the required bride wealth, and the girl would be legally handed over for marriage.

On the occasion of the handover ceremony, If the girl was a virgin, her aunt would accompany her. If she wasn't, the aunt, as an escort, would not accompany her. The purpose of the aunt would be to take the bedding and a goat that had never had sexual relations. She would walk by the house's back door on her way out. The goat was butchered and eaten without salt when they got home. Such celebrations were wonderful occasions for eating, drinking, dancing, and socializing.

Except for members of the Mamba and Ngabi clans, a man could not marry inside his own clan. They simply stated that there were a large number of them. Even then marriage occurred between distant clan members.

Death in the culture of Baganda

The Baganda were terrified of death. They had no faith in concepts like life after death. They would mourn and wail around the body whenever someone died. Weeping was vital because anyone who didn't weep and scream could be accused of murdering the corpse. The Baganda did not consider death to be a natural outcome. All of the deaths were blamed on wizards, sorcerers, and otherworldly spirits. As a result, a witch doctor would be consulted after practically every death.

After five days, the body was customarily buried. The body had to wait that long in the hopes of still containing the ingredient of life and therefore being able to resurrect. Some people, particularly women, would go so far as to pinch the corpse to see if it could feel pain. Women were thought to deteriorate faster than men, so they were typically buried earlier. A month of mourning would be observed, followed by funeral customs known as okwabya olumbe ten days later.

Okwabya olumbe was a large ceremonial feast to which all of the clan elders were invited, as well as a large number of individuals. It entails a lot of eating, drinking, dancing, and sometimes sexual activity among the attendees. If the deceased was the family's head, an heir would be installed at the same time. The heir apparent would be clad in ceremonial bark cloth and equipped with a spear and a stick, standing at the door. The elderly would then advise him as necessary and demand that he assist the beneficiaries, among other things. The children of the deceased would be wrapped in bark cloth and told to cry their hearts out at the plantation in order for the deceased's ghost to emerge.

Birth in Buganda

When a lady was pregnant, she would use the herb nalongo to enlarge her pubic parts. If the lady had already given birth, she would start using the herb during the seventh month of pregnancy. She would start using it at the sixth month of pregnancy if she was trying for the first time.

The kigoma (afterbirth) was buried by the entryway after giving birth. The objective of burying it was to keep it out of the hands of those who might want to use it for evil purposes like murdering the child or making the mother barren. The mother would be confined for three days after giving birth, but the length of time varied depending on when the umbilical cord dried. The husband would have sex with the wife for the first time after she gave birth after about two weeks. This was a rite associated with the kid's health, and the child would be named on that day. Following that, the lady would remain celibate for a period of time before resuming sexual relations with her husband.

The social division

A group of people known as the Bakopi lived at the bottom of the social ladder (serfs). Mukopi was defined by Fallers as "just a person who didn't matter." The Bakopi subsisted on the goodwill of the Baami (chiefs) and Balangira (princes), Buganda's other two social classes. They were reliant on land, yet they had no legal claim to it. As a result, a mukopi was essentially a servant to the mwami or Kabaka.

The chiefs, or Baami, as they were known in Baganda society, were the next class in ascending order. The Baami were not born Baami, but they may have become so through exceptional service and talent, or simply by royal appointment. In Buganda society, the Baami belonged to the middle class. The Baami class, in reality, demonstrates the mobility of the Kiganda system. The Bataka had the status of the Baami at first (Clan heads). After 1750, however, members of the Bakopi class began to be promoted to Baami. The Bakunga, Bataka, and Batongole are the three patterns that the Baami can be divided into.

The Balangira was Buganda society's highest social class. This was the aristocracy, whose claim to rule was founded on royal blood. At any one time, society would recognize the Kabaka, the queen mother (also known as Namasole, Nabijano, or Kanyabibambwa), Nalinya (also known as Lubuga), the Katikiiro, and the Kimbugwe. In Buganda, the group established their own class.

The Baganda's social characteristics

The first Baganda were supposed to be short and stocky, with a very big and flat nose. These traits can still be found among the Baganda today, but they have mostly lost their original structure. This is mostly due to their ability to blend in with various cultures. Many people from Rwanda, Burundi, Ankole, Toro, and Basoga have become Baganda over time, and they are proud of it.

The Baganda are generally proud of their community and are always willing to welcome people who wish to join them. They have a tendency to assume that their culture is superior to that of other Ugandans, and they frequently look down on their neighbors. Their attitude of superiority was stoked by colonialism, which made them allies in the oppression of others and then accorded them a privileged position under Uganda's protectorate.

Their women greet one other by kneeling as a symbol of respect. A Muganda would rarely pass another without greeting him or her, and they are quite picky about how they dress and walk. Eating would be governed by strict laws, and everyone, male and female, would sit on a mat. The male sat on one side, while the female sat backwards with her knees bent. It is believed that no one could leave the dining area until everyone had completed eating and without saying "Ofumbye nyo" to the person who cooked the meal and "ogabude" to the family's head.

Economy of the Baganda

Agriculturalists were the Baganda's main occupation. Bananas, sweet potatoes, cassava, yams, beans, cowpeas, and a variety of green vegetables were among the principal crops farmed. They had chickens, goats, sheep, and cattle as well.

Land was a valuable economic asset, and the kabaka was meant to own it all (King). Without warning, the kabaka could grant or take away land from anyone at any moment. Land was given in exchange for a political post, such as that of a Saza chief. Muluka chief or Gombolola chief The land would subsequently be given to the people under the Chief's jurisdiction to cultivate. In practice, though, the land still belonged to the Kabaka. Any chief who lost political authority would lose control of the land as well.

The Baganda were able to create beautiful works of art. Excellent craftsmen, bark cloth makers, weavers, and potters were among them. They manufactured fantastic mats as well as a wide range of baskets, pots, and chairs. Buganda is home to the top bark cloth manufacturers in Uganda today. Spears, shields, bows, and arrows were also created by them. They also created a variety of drums in various sizes and forms, as well as a variety of other musical instruments such as endingidi.

The Baganda were extremely proficient at fishing and hunting. Women handled the majority of household tasks and cultivation, while men concentrated on fighting, hunting, and fishing. Despite this, modern industrial production practices have pitted all of these activities against one another. Craft skills and markets have been badly hurt by industrialization, yet some can still be found in various sections of the country.

Buganda usurped Bunyoro's status as the center of interlacustrine trade in later times, during the middle of the 18th century. From the mid-nineteenth century, they traded ivory, dried bananas, whiteants, ceramics, and other crafts with the people of the interlacustrine region and the coastal Arabs. When colonialists arrived in the 1890s, the Baganda welcomed them with open arms and created a new economy based on trade and cash crops. The Baganda are now among Uganda's wealthiest people.

The political set-up of the Baganda

The Baganda had a centralized government that was the best organized in the interlacustrine region by 1750. The King, also known as Kabaka, was the head of state. Bataka had a lot of political clout in the past. They had a position that was essentially identical to that of the Kabaka, albeit they were subservient to him as Ssabataka. After 1750, however, the Kabaka rose to a position of political power considerably above that of the Bataka. The Kabaka's status was hereditary, but it was not limited to one clan because the monarch used to marry from as many clans as possible, encouraging allegiance to the throne in the sense that each of the fifty-two clans desired to produce the King one day.

The prime minister, known as the katikiro, the Mugema, the royal sister, Namasole, and the naval and army leaders, known as Gabunga and Mujasi, were among the others who held important political and social posts.

The Kingdom was organized into administrative entities known as Amasaza (counties), which were subdivided into Amagombolola (sub-counties), which were further subdivided into Emiluka (parishes), which were further subdivided into sub-parishes. The smallest unit was the Bukungu, which was essentially a village. The Kabaka nominated all chiefs at all levels, and they were directly responsible to him. He had the authority to select or dismiss any chief he wanted. Hereditary chieftainship was no longer hereditary after 1750. Chieftainship was granted on a clan basis, but only to those of distinction and merit.

Children of the Bakopi were sent to grow up in the chiefs' and Kabaka's courts as a form of apprenticeship under the okusenga system. Political posts were given to those who had proven their ability. The system entailed a great deal of servitude and hard labor, as well as harsh treatment from the leaders. If a person's services were exemplary, he could climb through the chiefly hierarchy from a commoner to the appointed Katikiro.

The succession culture of Baganda

There used to be succession issues after the death of the Kabaka. However, over time, structural changes were made to avoid such conflicts. The earliest example of such alterations was the king's decision to kill all of his sons and leave only one to inherit the crown after his death. This method was far too primitive to stand the test of time. Before he died, the incumbent king would nominate the person who would succeed him. It is said that such a nomination would be followed to the best of human ability. The Katikiro, the Kimbugwe (traditional Buruli saza chief) and Kasujja-Lujinga would make the final decision in such a scenario ( a chief traditionally appointed from the Lugave clan to look after the Balangira Bengoma-the heirs apparent). The Mituba were the other princes who were not heirs to the throne, and they were under the direct rule of an ancient prince named Sabalangira. The 1900 agreement has substantially altered this strategy. The Kabaka was supposed to be chosen by the Lukiiko and authorized by Her Majesty the Queen of England and Ireland, the Empress of India, and others. However, these prerequisites were just on paper. The final two kings, Mutesa II and his son Mutebi II, were chosen after being nominated by their fathers.

Death of the Kabaka

When the Kabaka died, his Majaguzo drums were transported away to a secure place until a new Kabaka was appointed. The drums were guarded by members of the Lugave clan. The sacred fire known as Gombolola, which had been kept blazing continuously at the palace entryway during the Kabaka's lifetime, would be extinguished. When the new kabaka is installed, it will be re-lit. Indeed, when a kabaka died, the usual term was "Omuliro gwe Buganda Guzikide," which meant "Buganda's fire has been extinguished."

The practice of linking the King's life with the burning of the fire is thought to have begun during Kintu's reign and continued until Mutesa II's escape from Lubiri palace in 1966. Senklole and Musoloza were the traditional keepers of the fire. The phrase "Agye omukono mu ngabo," which means "He has let go the shield," was also used to herald the Kabaka's death.

Burial of the Kabaka

When the Kabaka died, his body was properly wrapped in appropriate clothing and deposited in the Kabaka's house's "Twekobe" room. The two chiefs, Kangawo (title for Bulemezi's country chief) and Mugerere (country chief of Bugerere), would be placed in command of the body right away. The body would be embalmed for over six months before being buried. The Baganda thought that a man's spirit would always reside near his jaw bone. Because of this, the Kabaka's jawbone was removed from his body before burial and placed in a special shrine.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

5

Like

5

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

4

Love

4

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

1

Angry

1

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0