The Kakwa people

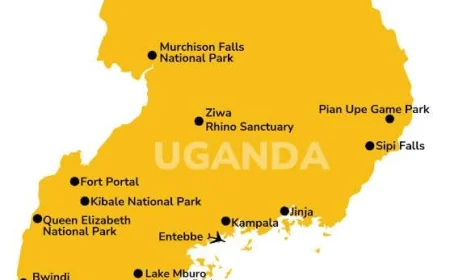

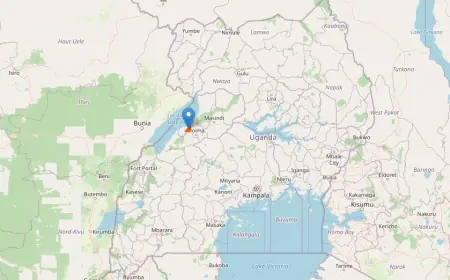

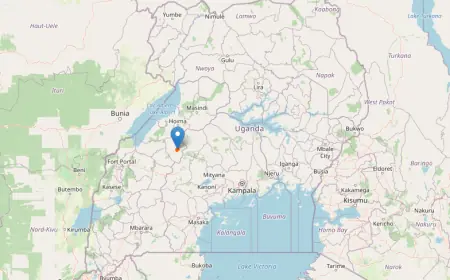

The Kakwa people are a Nilotic ethnic group that is mostly found west of the White Nile in northwestern Uganda, southwestern South Sudan, and the north-eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. They are a part of the Karo people.

The Kakwa are a people who inhabit Uganda's far north-west. They reside in the Arua district's Koboko county. The Kakwa are of Kushitic ancestry and are simply Nilotes in terms of ethics.

History of the Kakwa

They left East Africa (the Nubian region) from the city of Kawa, between the third and fourth cataracts of the Nile, according to Kakwa oral tradition. South Sudan comes first, then Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo farther south. In the Middle Ages, some of the Kakwa who bordered Uganda embraced Islam and the Maliki school of Sunni theology. In 1889, Tewfik Pasha, a descendent of the Egyptian Islamic ruler Khedive Ismail (Isma'il Pasha), annexed them into the Equatoria region. The area inhabited by the Kakwa people was included in the Uganda Protectorate as British colonial power spread into East Africa and Egypt.

When General Idi Amin, who was of Kakwa heritage, overthrew the Ugandan government in a coup, the Kakwa people gained recognition on a global scale. He appointed members of his ethnic group and Nubians to significant military and civil positions in his administration. He detained and assassinated representatives of other ethnic groups, like the Acholi and Lango people, whose loyalty he questioned. The Sudanese Kakwa in the country's first civil war were also given weapons and financial support by Idi Amin. Later, other human rights violations were alleged against Kakwa government officials under Idi Amin. Many Kakwa people were killed in retaliatory killings when Amin was overthrown in 1979, which led to additional Kakwa people leaving the region and fleeing to Sudan. However, they have now returned to their native areas in the West Nile region of northern Uganda.

Origins of Kakwa

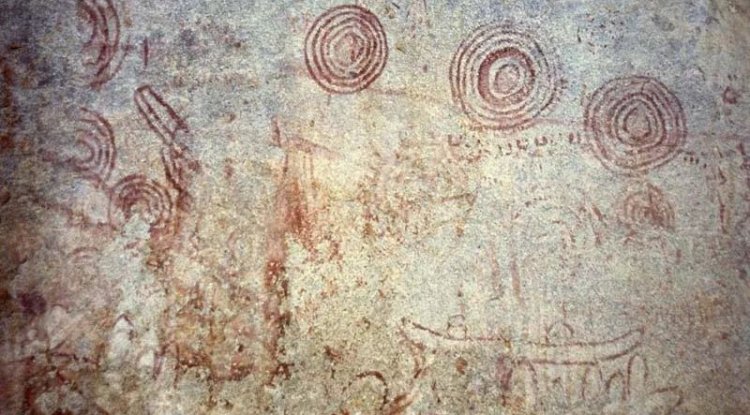

Regarding the Kakwa's beginnings, there are primarily two traditions. According to one portion of folklore, Yeki was the ancestor of the Kakwa people of Uganda. He is claimed to have moved to Mt. Liru in Koboko from Karobe Hill in southern Sudan. According to this story, Yeki had seven kids, one of whom was caught biting his brothers. As a result, Yeki is claimed to have given him the nickname Kakwan ji, which means biter. According to legend, Yeki's descendants adopted the plural form and called themselves Kakwa.

According to the second legend, the Kakwa were formerly referred to as Kui. According to legend, the Kui were ferocious warriors who severely punished their adversaries. Since then, the Kui have claimed to have given themselves the appellation "Kakwa" because their furious attacks resembled tooth bites. The vast majority of Kakwa in Koboko adhere fervently to this custom.

Almost all of the Kakwa clans in Koboko, a portion of Maracha, and Aringa can trace their roots back to Loloyi, yet none of them can pinpoint exactly what or where Loloyi is. The Kakwa can be linked linguistically to the southern Sudanese Bari. In fact, the Kakwa continue to hold on to their belief that they are related to the Kuku, Mundari, Nyangwar, Pojuru, and even Karamojong.

According to the Koboko story, the first Kakwa ancestors originated in the direction of Ethiopia. According to this tradition, the Kakwa and Bari split from one another at an unknown point. They were allegedly divided into Bari County, east of the Nile, according to widespread speculation. They may have split off from the Bari at Kapoeta given that they are simple Nilotics like the Iteso and the Karimojong.

Kakwa social and political set-up

The Kakwa had segmented political structures. In the absence of a centralized authority, clans served as the fundamental social and political entities. Each clan had adequate historic loyalty and was politically distinct from the others.

A chief known as matter presided over each clan. The chief went under the names Buratyo and Ba Ambogo, among other clans. The chief was the highest political official, and the Temejik, or clan elders, were the officers directly below him. The Temejik were frequently in charge of a subclan and were related to the chief since they were either brothers or uncles.

Both a political person and a rainmaker, the chief. The Kakwa of Koboko continue to acknowledge that some of them had served as chiefs. Only the rainmaking tribes were eligible for chieftainship, and the chief would concurrently hold the titles of chief of the land and chief of the rain.

There were some Kakwa clans, nevertheless, that lacked rainmakers. Ludara Kakwa is one illustration. They cited the fact that Solo, their ancestor, did not come from a rainmaking family as the justification. The roles of the head of the land and the chief of the rain were divided in these clans. The role of the rain chief was given to someone else who wasn't the chief. It was uncommon to find a chief who was not also a rainmaker, though.

The chief's status was inherited in the matrilineal Kakwa culture. The chief's position was not inherited among the clans that did not produce rain, nevertheless. A borrowed rainmaker had little political sway, but clans without them may borrow them from other clans. Instead, he would receive payment for his services.

Clientship

The Kakwa did not have clearly defined classes, although there were both upper and lower class members of the community. House staff, cattle herders, and young children made up the lowest classes.

They would stay with an upper class person even after they got married if they took good care of their dependents. A client, however, would depart and look for another master if he were handled hostilely or in a way that made him appear subordinate. If a client was referred to as monyatio, which means "stranger in the home," they would typically leave and go somewhere else. When a client reached marriageable age, his master would cover the cost of his bride. He would then become a member of the family.

Choosing and installing a chief

A customary rite of some kind had to be carried out before a person could become the chieftain. A chief typically had a secret bead that his forebears had handed on to him. Without his sons' knowledge, the chief would frequently place the bead in food and invite them to eat. The person who found the bead and gave it to his father would succeed him. His father made him carry his primary stick and stool wherever he went after that. He was also expected to closely watch what his father did in order to familiarize himself with his upcoming duties.If it was well recognized that the nominee lacked responsibility, the elders had the authority to reject him. Although there were various methods, this one was typically used to choose a chieftain's successor.

If a leader didn't have any sons, his nearest relative would take over. If a chief passed away, leaving a young son, a regent would be chosen to take over until the boy reached adulthood. A similar incident took place in Media in the late 1890s. When Chief Bongo passed away, his young son Baba was named chief-elect. In the meantime, Ali Kenyi, his nephew, was chosen as regent. Baba was unfortunate, though, for the Belgians arrived before he could effectively assume his job. They worked together, and Ali Kenyi kept the chair.

All the clan members would congregate at the main residence known as Kadina mata for the installation of the chief. It was usual for the elderly to sit alone and request the ancestors' blessings so that the new chief might lead his people in peace and prosperity as they brought food and drink. Dancing and celebration would then ensue.

Role of the chief

The clan's chief had to counsel his clan to prevent its cattle from grazing on the crops of other clans and defend the clan's hunting areas from attack by other clans. In the case of external assault and defeat, it was his responsibility to evacuate his population and to try to negotiate a peaceful resolution. In addition, he served as the council of elders' advisor. He didn't require the elders' counsel if he operated in his capacity as a rainmaker. This was because it was thought that a common man, no matter how old he might be, did not have the ability to summon rain or execute reproductive rituals.

Military setup of Kakwa

The chief didn't maintain an army. Each chieftainship did, however, have a military commander known as the Jokwe. In order to get information from the clan's ancestors regarding the military prowess of the opposing clan before preparing for war, the chief and the Jokwe would consult the elders and perform a ritual ceremony.

A chicken was tied to the middle of a circle that was drawn on the ground as part of the ritual. Signs of either success or defeat would alternatively be placed around the circle's perimeter. After that, the chicken in the center of the circle would be killed. The leader would warn the entire clan not to go to war if it perished, or came close to "defeat." The leader of the rival clan would then be approached to begin peace talks.The clan had to go to fight, regardless of how weak it was. However, if the chicken died close to "winning," it was thought that the ancestors' spirits would support them and give them the power to prevail.

In some situations, such among the Leiko, the wives would go to battle with their husbands. According to legend, these ladies were spared throughout the conflict because it was thought that killing a woman would offend the ancestors, who would then turn the man's adversaries against him far sooner than he would have anticipated. Women were sent into battle in order for their husbands to hear them yell and cheer them on. Until the conflict was ended, they would also remove the wounded and the dead and hide them.

The Kakwa Judicial system

Clan elders mediated conflicts. The chief would be notified of the most serious situations. Children and women would not participate in making decisions. Contrary to the Lugbara, who forbade the women and children from remaining close to the court, the Kakwa let them attend. Apart from when they were testifying as witnesses, they were just required to sit down and glisten.

It was frequently difficult to decide certain critical instances. Murder and adultery were two serious offenses. In the event that a guy was discovered to be having an affair, he would be executed without a trial. The same was true for any time spent judging a thief. He would be put to death, as they claimed, "in the way foxes are put to death," or in a manner akin to "mob justice." When a member of another clan was killed, it would cause conflict between the clans, and the victim wasn't mourned until enough vengeance had been taken.

Retaliation was frowned upon if one killed a member of a clan. The murderer would provide one or two cows as payment. People frequently confessed in the open by saying, "I killed a, b, and c because of x, y, and z. Two tests would be performed to determine whether the accused was guilty or not if he rejected the accusations. Following the accused's admission of innocence in situations involving witchcraft or poisoning, the following steps would be taken:

A woman would be led to the stream to demonstrate her innocence if she was charged with poisoning her husband but denied it. The members of the woman's clan and the husband's family would also visit the stream. After that, the woman would be given jja or kuru (seeds of wild plants) to eat and be instructed to drink a lot of water.

She was expected to throw up all the water if she was innocent. However, if she had actually poisoned the spouse, she wouldn't have thrown up and her stomach would have started to expand. At that moment, she would be murdered in front of her own clansmen by the husband's family. But if she threw up the water, her family would stand up for her, and if she wasn't made whole for this cruelty, war could easily break out between the two clans. The husband's family might repair the woman's reputation and reinstate order with the payment of a bull or a cow.

If two people were discovered having extramarital affairs, the boy would be held hostage until his folks paid a ransom, typically in the form of a cow or four goats. Additionally, the boy would frequently be coerced into marrying the female. These were straightforward situations that couldn't spark a clan conflict.

Economy

The Kakwa's economy was based primarily on subsistence farming, though some families also engaged in mixed farming. In addition to farming, they raised sheep, goats, and cattle. Their main food crops have historically been millet, sorghum, and a kind of bean called burusu. The Kakwa ate these as a matter of course. Pawpaws, maize, and cassava have been added to them as a supplement. Cassava is claimed to have arrived with the arrival of the Belgians and the logo of a Zaire-born ethnic group. The British are credited with introducing pawpaws.

Traditionally, laree fields called vya or litika, which were dug on a community basis, were used to seed millet, sorghum, and burusu. In Kakwa's economy, women played a lesser role. The men built and repaired the buildings, looked after the animals, plowed the fields, and sowed the seeds. Women would clean and store the crops in the granaries as well as remove the trash from the planted fields.

The women worked hard at manufacturing pottery, salt, and baskets. Native plants called morubo and bukuli were used to make salt. After being burned, the remains of these plants would be placed in a container with numerous holes at the bottom, and water would be poured over them. Through the openings, the briny liquid would drain into another container at the bottom.

The Nyangaila clan specialized in iron smelting and produced a wide range of iron tools, including spears, knives, hoes, and other equipment. The Kakwa defined wealth as "how many granaries full of food" one had in their compound and "how many livestock one had in one's kraal." In the event of famine, which was frequent, people would go to a region where there was lots of food.

The Lifestyle of Kakwa

Corn, millet, cassava, fishing, and cattle have traditionally been the main sources of income for the Kakwa people. Males create councils of the elders, who bind the traditional villages of Kakwa together by their ancestry. The Kakwa people's [cultural value systems and lifestyle] include polygyny, which is tolerated and practiced, as well as Christian and Islamic traditions.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

2

Like

2

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

3

Wow

3