The Banyankole

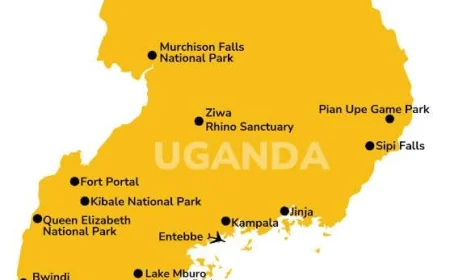

The word Ankole was introduced by British colonial administrators to describe the bigger kingdom which was formed by adding to the original Nkore, the former independent kingdoms of Igara, Sheema, Buhweju and parts of Mpororo (Runyankore is native language in these areas). Ankole kingdom was one of four kingdoms that make up what is now Uganda.

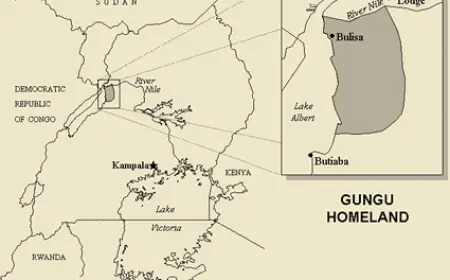

Banyankole is a bantu tribe. They live in the current western Ugandan districts of Mbarara, Bushenyi, and Ntungamo. In the Rukungiri District, people from the current nations of Rujumbura and Rubando have a same culture. The term Nkore is thought to have been used in the 17th century as a result of the disastrous invasion of Kaaro-Karungi by Chawaali, the then Omukama of Bunyoro-Kitara. Originally, Ankole was known as Kaaro-Karungi. The larger kingdom that was created by uniting the old Nkore with the erstwhile independent kingdoms of Igara, Sheema, Buhweju, and some of Mpororo was called Ankole by British colonial administrators.

The Origins of Banyankole

The Banyankole can be traced back to the Congo region, just like other Bantu ethnicities. According to legend, Ruhanga (the creator), who is said to have descended from heaven to rule the world, was the first person to live in Ankole. It is thought that Ruhanga travelled with his three sons, Kairu, Kakama, and Kahima. According to a legend, Ruhanga conducted a test to determine which of his sons would succeed him as heir. According to legend, the test involved having pots filled with milk on their laps the whole night. The youngest son, Kakama, is supposed to have been the first to pass the exam, followed by Kahima, and then the eldest son, Kairu. Based on how well they did in the exam, Ruhanga is supposed to have ordered Kairu and Kahima to serve their brother Kakama. He then returned to heaven, leaving Kakama, or Ruhanga, as he was also known, in charge of the realm. In this myth, class stratification in Ankole culture is depicted. It was created to convince the Bairu that their role as the Bahima's underservants was supernatural.

Social stratification

The Banyankole society was divided into two groups: the Bairu (agriculturalists) and the Bahima (pastoralists). The Bahima had a dominance structure akin to a caste over the Bairu. The pastoral and agricultural pillars of society formed a dual pyramid. The clans cut over both the Bairu and the Bahima inside the two groupings of castes (I refer to them as castes rather than classes because among the Bahima and Bairu there were those who had something in common). Both groups acknowledged having a common ancestor. There was a widespread perception that a hoe and a cow are what define a mwiru (plural Bairu) and a muhima (plural Bahima). This kind of concept was not particularly true because neither the simple act of getting cows nor the loss of cows would instantly change someone from being a Mwiru into a Muhima. A Muhima with a small herd of cattle was known as a Murasi. A Mwambari was a Mwiru who kept cattle.

Both groups shared a living space and were reliant on one another. The Bahima and the Bairu exchanged cattle products, while the Bairu also provided agricultural items to the Bahima. This was due to the fact that the Bahima would also want agricultural items from the Bairu, as well as local beer, while the Bairu required milk, meat, hides, and other animal products from the Bahima.

The Language

Runyankole is the language spoken by the Banyankole. Runyankole is home to the two most read newspapers, Orumuri and Entatsi. The primary language of broadcast on almost all radio and television stations in western Uganda is Runyankore. It is taught and used as a medium of education in kindergarten and elementary schools. The Banyankole people speak Runyankore, a Bantu language (the Ankole people of Uganda). The districts of Mbarara, Bushenyi, Ntungamo, Kiruhura, Ibanda, Isingiro, Kanungu, and Rukungiri are where it is most commonly used.Students that are interested in anthropology, NGO work, exploration and travel, government work, African languages and literature, African art, African history, African linguistics, and sociolinguistics will find Runyankole to be a beneficial language to learn. Typical Runyankole greetings include the following: Agandi......................................... How are you doing? [General and timeless greeting but more common among age mates]

Nimarungi.................................... I am fine/I am ok. [specific reply to Agandi]

Osibiregye..................................How is your day going? [Daytime general greeting used at least from midday to late evening hours]

Orairegye/Orireota ......................How was your night/ How did your night go? [General morning greeting]

Origye/Oriota...............................How are you doing? [Common timeless greeting more common among age mates]

Ndigye/Ndiaho.............................I am fine/I am ok [It is specific reply to Origye/Oriota]

Kaije buhorogye? .........................Is it peace/How have you been in a long time? [A very formal, ageless, and general greeting used after a long absence]

Eeh/Ego ........................................Yes, it is peace [reply to Kaije buhorogye]

Ori buhoro ...........................Are you peaceful/Are you at peace/ Are you alright? [A very formal greeting used especially by an elder to his/her fellow elders and people of other ages]

Eeh (Sebo ’Sir’ /Nyabo ’Mum’) .................................Yes Sir/Mum, I am peaceful. [Reply to Buhoro]

Marriage among Banyankole

In the past, it was customary for the parents of the boy and the girl to arrange the marriage, often without the girls' knowledge. Usually, the boy's parents would take the initiative, and after receiving a suitable bride's riches, plans would be made to bring the bride home. When a girl's older sister or sisters were still single, she was traditionally not eligible for marriage. If a younger sister received a marriage proposal, it is stated that the girl's parents would manage events so that they would conceal and send the older sister to the wedding ceremony. The bridegroom was not expected to ask questions once he learned about it. If he could afford it, he could go ahead and pay the extra bridewealth before getting married to the younger sister. The bride's fortune had to be paid in full, and the father had to cover all other expenses related to setting up his son's marriage.

The girl would be attended by several people, including her aunt, throughout the wedding ceremony. According to some traditions, the husband would have intercourse with the aunt before moving on to the bride. According to another legend, the aunt's job was to witness or hear the bridegroom and her niece engaging in sexual activity in order to demonstrate the groom's potency.Since girls in Ankole were intended to be virgins until marriage, it is stated that her responsibility was to give the girl advice on how to start a home. The first custom is untrue because the aunt is typically an elderly woman who is about the same age as the mother of the groom, but the other two customs are accurate. If the girl's parents knew that their daughter wasn't a virgin, they would formally inform the husband by presenting the girl with a perforated coin or another hollow object, among other presents.

Oruhoko

Okuteera oruhoko was a term used to describe the practice of forcing a girl into an impromptu marriage without her consent or much planning when she had purposefully refused to love him or when she had rejected a particular boy.

The Ankole traditional civilization was characterised by the practice of okuteera oruhoko, although there are still signs of it now. This technique was frowned upon by society, but it was nonetheless prevalent and beneficial. However, the perpetrator was required to pay a sizable amount of wealth as a fine. This technique was carried out in a variety of ways.

Using a cock was one such method. A boy who wanted to marry a girl who had turned him down would take a cock, go to the girl's home, hurl the cock in the yard, and then flee. It was believed and feared that should the cock crow while the girl was still at home, refusing to follow the boy or making superfluous preparations, she or another member of the family would quickly die. The girl had to be rushed to the boy's house at once.

Another kind of Oruhoko was performed by applying millet flour to the girl's face. The boy would take some flour from the winnowing tray, which is used to catch the flour as it comes off the grinding stone, and spread it over the girl's face if he happened to see her grinding millet. Any delays or justifications would result in identical results to those used in the procedures mentioned above, so the kid would flee and prompt arrangements would be made to send him to the girl.

There were three other ways to perform the okuteera oruhuko, particularly among the Bahima. One of them involved the lad tying a rope around the girl's neck and declaring in front of everyone that he had done so. The second involved placing an orwihura plant on the girl's head, and the third had the boy milking her while sprinkling milk on her face. It should be noted that this custom could only take place if the boy and girl belonged to separate clans.

Oruhuko was a harmful and humiliating custom. Boys who had no other options typically tried it. However, it was typically done so swiftly that the boy would have vanished before the girl's relatives could organise, even if the boy was not fortunate enough to elude and run quicker than the girl's family. The guy was typically punished by being given an excessive amount of bride wealth. He would be charged twice as much, if not more. If the marriage failed, the extra cows that were invoiced were not repaid.

Births

The Banyankole did not practice any unusual birth rituals. Normally, a woman would be sent to her mother when she was about to give birth for the first time. Women who were bold, as most of them were, could give birth on their own without the assistance of a midwife. An acting midwife, typically an elderly woman, would be called in, nevertheless, if something went wrong.

Some medication would be given to the mother if the afterbirth resisted emerging freely and immediately after the kid. The husband of the woman was supposed to climb to the top of the house with a mortar, sound an alarm, and then slide the mortar down from the top of the house if the usual herbs failed to bring it out.

Naming of a child

After birth, the kid could be given a name. After the mother had concluded her days of confinement, the custom was known as ekiriri. If the child was a boy, the mother would stay in her room for four days; if it was a girl, she would stay in her room for three days. The couple would continue their sexual relationship, known as okucwa eizaire, after three or four days, depending on the situation. The parents' personal histories, the kid's birth time, the days of the week, the location of the birth, or the name of an ancestor all had an impact on the name that was given to the child. The child's mother, grandfather, and father would all choose the name. The father's preference, however, typically prevailed.

The names provided were nouns or verbs that may be used in everyday speech. The names frequently also expressed the givers' emotional states. For instance, the Banyoro name Kaheeru represented the husband's suspicion that the mother had the kid outside of the family. The woman might have sex with her in-laws and possibly have children by them in the old Ankole culture. These kids received the same treatment as the rest of the family's kids.

Deaths

The Banyankole did not consider death to be a natural occurrence. They believed that sorcery, bad luck, and neighbourly animosity were to blame for death. Tihariho mufu atarogyirwe was even one of their proverbs. "Nobody dies without being enchanted," in other words. They had a hard time accepting the idea that a man might pass away without the aid of witchcraft or the malice of others. As a result, the people who were impacted by a death would seek the advice of a witch doctor to identify the cause of the death.

Typically, a deceased person would remain in the home for however long it would take the relevant family members to gather. An individual would be buried among the Bairu, either in the compound or in the plantation. He would be buried in the kraal among the Bahima. The bodies were buried facing the east in the afternoons, on average. While a male was made to lie on his right, a female was forced to lie on her left. A woman was given three days of mourning after burial, whereas a man was given four. All the neighbours and the deceased's family would stay put and camp out at the deceased's house throughout the days of grief.

The entire neighbourhood avoided digging and manual labour during this time since it was thought that if anyone did so, he would bring hail storms that would destroy the entire hamlet. A person like that may likewise be thought of as a sorcerer, and they might be easily suspected of being responsible for the death of the person who had just been buried. However, the neighbours' refusal to dig or perform other labour-intensive tasks was intended to comfort the kin.

To end the days of mourning, the dead man's leading bill would be killed and eaten if he was the head of the household. If the deceased was very old and had grandchildren, additional ritual ceremonies would be performed. If a person passed away harbouring resentment toward a member of their family, they were buried with various items to occupy their ghost and prevent them from coming back to haunt those people.

For single people and those who committed suicide, there were special funeral services. It was frowned upon for someone to take their own life. It was very difficult to bury someone who had committed suicide. A woman who had reached menopause would cut the body from a tree (encurazaara). Such a woman was armed with charms to the teeth. In fact, it was thought that whoever cut the rope used by the suicide would soon pass away as well.

According to tradition, it was occasionally impossible to touch the bodies of suicide victims. In order for the corpse to fall into the grave when the rope was cut, a grave was dug directly beneath it. After that, the grave was simply covered. There wouldn't be a funeral or any traditional mourning customs. The victim would be burned alive along with the tree he hugged. No part of that tree would be used as firewood by the suicide victim's family.

Additionally, there were specific formalities for a spinster's funeral. It was thought that if such a girl passed away, her ghost would return to haunt the living because she had passed away unhappy. Before the body was taken for burial, one of the dead girl's brothers was required to pretend to make out with the corpse in order to appease the spirit and prevent its evil repercussions. Ogyeza empango ahamutwe was the name given to this action.The body was then buried after being placed by the back door. It is said that if a man passed away without a wife, she would be represented by a banana stem and buried with him. This was thought to appease the ghost of the deceased man and its wicked judgments on the living. Also entered through the back door was the body.

Blood brotherhood

Blood brotherhood was a custom among the Banyankole. In the okikora omukago ceremony, someone would become a blood brother. The two people had to sit on a mat so closely together that their legs would overlap for the actual ceremony. They would hold an omurinzi tree sprout and an ejubwe-type grass sprout in their right hands (erythina tomentosa). The Bairu would also contain an omutosa (fig) tree sprout (ficus eryobotrioides).

The master of ceremonies would make a tiny cut to each man's right naval. Each person's hands were placed on the blood-stained end of the omurinzi tree and the ejubwe grass. Only the mutoma sprout was used for the Bahima. Then each man would hold the other's hand with his left, and they would both swallow the blood, the milk, or the blood and the millet flour in each other's hands at the same time. This procedure was used with the Bairu.Blood brotherhood could not be made between people of the same clan because, naturally, they would be regarded as brothers. Blood brothers would treat each other as real brothers in every respect.

Banyankole Political set-up

The government of the Banyankole was centralised. There was a king named Omugabe at the top of the political food chain. A prime minister by the name of Enganzi served beneath him. Then there were the Abakuru b'ebyanga, or provincial chiefs. They were followed by chiefs who were in charge of parish and sub-parish level local affairs.

The king's position was inherited. The King had to be a member of the Bahinda royal family, who claimed to be descended from Njunaki's son, Ruhanga. There were frequent succession disputes to decide who would take the throne after a king died. The new king would then be installed following a lengthy ceremony. Some of a king's wives would kill themselves or be forced to do so after his death. In the royal court, some of the servants would also kill themselves. According to legend, some members of the Baingo clan would have also been killed in the past in order to join the King in the afterlife. The king's body was also known as omuguta to distinguish it from a regular person's corpse, which was called omurambo. The Bayangwe clan, posing as the Abahitsi for the occasion, specially buried it. Instead of saying Omugabe afire, which is the proper Runyankole term, one would say that Omugabe ataahize to convey the message that the King has passed away.

The Royal Regalia

A spear and drums made up Ankole's royal regalia. The Bagyendanwa royal drum served as the primary instrument of power. Wamala, the final Muchwezi emperor, is thought to have made this drum. Only when a new King was installed was this drum beaten. It had a unique hut, and closing the hut was frowned upon. There was always a fire that kept going for Bagyendanwa, and the only way it could be put out was if the King passed away. The accompanying drums included the kabembura, Nyakashija, eigura, kooma, and Njeru ya Buremba, which was acquired from the Buzimba kingdom. The drum also had its own cows.

Religion

Ruhanga was the Banyankole's concept of the Supreme Being (creator). Ruhanga's home was purported to be in heaven, just above the clouds. All things were said to be created and given by Ruhanga. However, it was thought that evil people could use black magic to thwart Ruhanga's wishes and bring about sickness, famine, death, or even bareness among the people and in the land.

Ruhanga's concept found a more primitive expression in the cult of Emandwa. They were easily approachable in times of need because they were gods to various families and clans in particular. The family gods were said to reside in the shrines that belonged to each family. A gourd filled with beer and some small pieces of meat were placed in the Mandwa shrine whenever beer was made or a goat was killed. The family members would perform okubandwa rituals as a means of pleading with the gods to prevent sickness or misfortune in the event of sickness or misfortune.

Entereko

By pressing ripe bananas, combining the juice with water and sorghum, and then allowing the mixture to ferment overnight in a wooden vessel called an obwato, the Banyankole made beer. Every social communal activity or other event required beer. The Banyankole had what they called entereko whenever beer was produced. As a sign of belonging and good neighbourliness, anyone who brewed beer was required to set aside some for the neighbours. Entereko was the name of this tense beer.

He would typically call his neighbours and serve them the reserved beer one or two days after someone had brewed beer. Anyone who disregarded this custom was regarded as a bad neighbour because it was so crucial. In the event of need, he wouldn't receive the assistance of the neighbours. The men would talk about significant issues of substance during the entereko service that specifically affected their region, the kingdom, and beyond. Dancing would be among the many celebrations. Men and women would both take part in the Banyankore's traditional dance, known as ekyitaguriro. The Bahima also performed competitive recitals and sang songs about cattle and displayed bravery in offensive and defensive wars.

Millet was a common food among the Banyankole. Bananas, potatoes, and cassava were added to it. The ability of a family to maintain year-round food supplies was a sign of wealth and prosperity. Beans, peas, and groundnuts served as the main sauces, along with a variety of greens like eshuwiga, enyabutongo, dodo, ekyijamba, omugobe, and omuriri, as well as meat from both domestic and wild animals.A family was not respected if it was unable to produce or store enough food for the majority of the year. In times of scarcity, a woman would go work in another family's garden for food with her daughters. This procedure was known as okushaka. It was extremely humiliating and made the affected family look bad. In fact, it would make the family's daughters less attractive to potential suitors because it would be widely known in the neighbourhood that they came from a lax household.

For special occasions, millet and meat were prepared. Cassava and potatoes were not considered respectable foods and could not be served to guests or eaten unless there was a true food shortage. Families rarely ate their entire meal together. The family head, however, was not permitted to consume leftovers. In addition, boys and men were cautioned against consuming burned potatoes. Because it was so sweet, a man might have been tempted to abandon his tasks and return home whenever he thought of its sweetness while out on a hunt or at work. Women and children alike consume this food. Enjuba, a milk and blood dish, was the main diet of the Bahima. In addition, they would barter milk and ghee from the farmers for potatoes, cassava, and matooke. The Bahima could simply survive on milk and blood during genuine food shortages.

Method of counting

The Banyankole used a unique system of counting. They were able to count with their fingers from one to ten. By displaying just the forefinger, one was denoted. The first and second fingers were used to signify two, the last and third fingers to signify three, and the clenched fist with the thumb tucked inside to signify five. The first, second, and third fingers were displayed to denote the number six. Holding down the third finger while displaying the first, middle, and last fingers suggested the number seven. Snapping the first fingers of both hands together implied eight, clenching the middle finger with the thumb meant nine, and making a fist with the thumb on the outside meant ten.

After this, Read : Exploring the Distinct Identities of Bahima and Bairu

What's Your Reaction?

Like

4

Like

4

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

6

Love

6

Funny

1

Funny

1

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

1

Sad

1

Wow

2

Wow

2