Banyarwanda: The Supra Ethnicity of Uganda

The Banyarwanda in Uganda are mainly the descendants of the people who lived in the former provinces of the Rwanda Empire that were annexed by the British colonial authorities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Imagine you are a Banyarwanda, a member of a Bantu ethnolinguistic group that spans across several countries in the African Great Lakes region. You speak Kinyarwanda, a language that shares a common prefix “RA” with other related languages such as Runyankore, Rukiga, and Rufumbira. You trace your ancestry to the ancient Rwandan Empire, which was once a powerful and prosperous kingdom that dominated the region. You have a rich and diverse culture that celebrates the bond of brethren, or "Ubuvandimwe.”.

Imagine you are living in Uganda, a country that has over 56 recognized indigenous tribes, each with its own history, identity, and rights. You are one of the 11 million Banyarwanda. You are a citizen of Uganda, but you are often mistaken or categorized as a foreigner because of the name of your tribe. You face discrimination and exclusion from the economy and public service of your country. You are denied access to national identity cards and passports, which are essential documents for every Ugandan. You are tired of being treated as an outsider, and you want to change your tribe name to "Abavandimwe," which means brethren in Kinyarwanda.

This is the reality of many Banyarwanda in Uganda, who are struggling to assert their identity and rights in a country that has a history of ethnic conflicts and violence. In this article, we will explore the origins, history, and challenges of the Banyarwanda in Uganda and how they are trying to rename their tribe to gain recognition and acceptance.

Origins and History

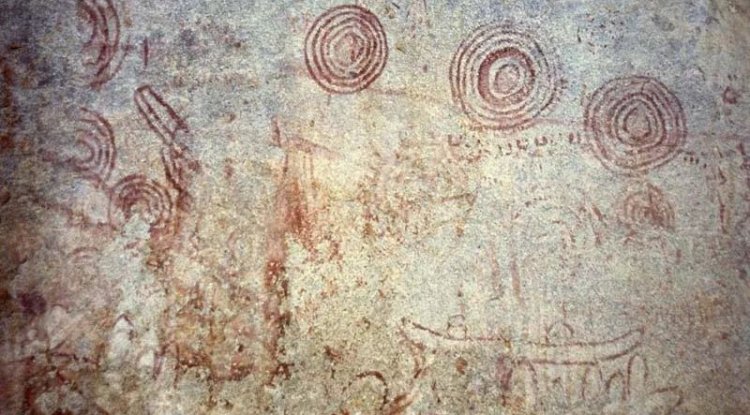

The Banyarwanda are descended from a diverse group of people who settled in the area through a series of migrations. The earliest known inhabitants of the African Great Lakes area were a sparse group of hunter-gatherers who lived in the late Stone Age. They were followed by a larger population of early Iron Age settlers, who produced dimpled pottery and iron tools. According to some theories, these early inhabitants were the ancestors of the Twa (or Batwa), a group of aboriginal pygmy hunter-gatherers who remain in the area today.

Between 700 BC and 1500 AD, a number of Bantu groups migrated into the territory and began to clear forest land for agriculture . Some state that the forest-dwelling Twa lost much of their habitat and moved to the slopes of mountains. Others argue that the Twa came to exist as a group who were in a close client relationship with the farmer populations and that perceived physical distinctions are not from separate origins but caused by the advantages of small stature in forest hunting leading to more opportunities to have children and those of higher stature leaving the group.

The Bantu migrations also brought the ancestors of the Hutu and the Tutsi, who are the two major ethnic groups of the Banyarwanda. The Hutu are generally considered to be the descendants of the original Bantu farmers, who adopted the language and culture of the region. The Tutsi are generally considered to be the descendants of a later wave of Bantu pastoralists who intermarried with the local population and established a feudal monarchy over the Hutu and the Twa .

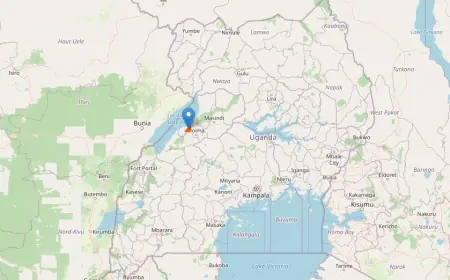

The Rwanda Empire emerged in the 15th century, under the rule of the Tutsi kings, or mwami. The empire expanded its territory and influence through conquest and alliances and reached its peak in the 19th century, under the reign of Mwami Kigeli Rwabugiri. The empire encompassed most of present-day Rwanda, Burundi, and parts of Uganda, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo .

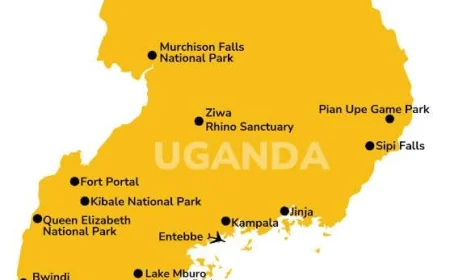

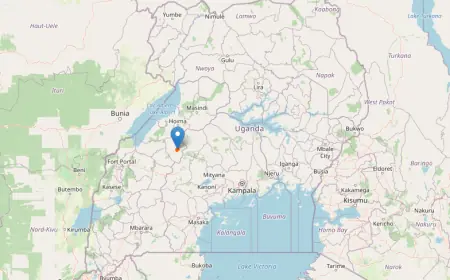

The Banyarwanda in Uganda are mainly the descendants of the people who lived in the former provinces of the Rwanda Empire that were annexed by the British colonial authorities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These provinces include Ankole, Kigezi, Toro, and Bunyoro, which are now part of Uganda. The Banyarwanda in Uganda also include the refugees and migrants who fled from Rwanda and Burundi due to violence and instability in those countries, especially in the 1960s and 1990s .

Banyarwanda food and drinks

The Banyarwanda are pastoralists and agriculturalists. They raise livestock and cultivate millet, cassava, maize, and vegetables. Their major foods include millet, cassava, and milk. Millet is known as "Uburo", cassava as "Umwumbati", and milk as "Amata". Bread is manufactured from either millet or cassava flour. Cassava can also be cooked fresh. This bread and boiling cassava are eaten with "Ibihyimbo" beans, milk, and milk products. Their traditional drinks include milk and urwagwa, a banana-based beverage.

Kinyarwanda Dress code

Banyarwanda men's dress code is a shirt and trousers with a drape tied diagonally at the shoulder and carrying a walking staff. Women wear umushanana, which is a dress or skirt with an over-the-shoulder drape.

Rwandan men had the Amasunzu haircut, which featured intricate crests.

Music and dance

Music and dance are essential components of Banyarwanda ceremonies, festivals, social gatherings, and storytelling. The most well-known traditional dance is a highly choreographed routine made up of three parts: the umushagiriro, or cow dance, done by women; the intore, or hero dance, performed by men; and the drumming, which is typically performed by men on ingoma drums. Music has traditionally been transmitted orally, with styles ranging among the Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa. Drums are extremely important; royal drummers held a high rank in the king's court. Drummers form groups of varied sizes, typically ranging from seven to nine players.

Language and Literature

Kinyarwanda, often referred to as the Rwanda language, is the linguistic pulse of the Banyarwanda people. Predominantly spoken in Rwanda, it also resonates through the Congo and Uganda. As a member of the Bantu family, Kinyarwanda shares a mutual intelligence with Kirundi and Ha, forming the Rwanda-Rundi linguistic tapestry. With over 10 million speakers for Kinyarwanda and approximately 20 million for the Rwanda-Rundi group, its voice is one of the most widespread among the Bantu languages. The echoes of the Bantu expansion from Cameroon are believed to have carried Kinyarwanda into the region, supplanting the indigenous tongues of the Twa and possibly the original language of the Tutsi, who are thought to have Nilotic linguistic roots.

The Linguistic Structure of Kinyarwanda

Kinyarwanda’s tonal, agglutinative nature weaves words from morphemes, including prefixes and stems. Its nouns are categorized into sixteen classes, reflecting singular and plural forms. Certain classes are reserved for specific noun types; for instance, classes 1 and 2 are dedicated to human-related nouns, while classes 7, 8, and 11 denote larger entities, and class 14 encapsulates abstract concepts. Adjectives harmonize with nouns by adopting corresponding prefixes. For example, “abantu” (people), a class 2 noun, becomes “abantu babiri” (two people) when combined with the adjective “-biri” (two). Similarly, “ibintu” (things), a class 4 noun, transforms into “ibintu bibiri” (two things).

The Oral Tradition of the Banyarwanda

The Banyarwanda’s literary roots are not entrenched in written texts but in a rich oral tradition. The colonial era introduced writing, but French dominated the literary scene. Despite this, the Banyarwanda’s oral heritage thrived, with royal poets, known as abasizi, reciting verses that celebrated the monarchy, spirituality, and valor. This oral legacy served as both a conduit for historical and ethical teachings and a source of entertainment. Alexis Kagame (1912–1981) stands as a beacon of Rwandan literature, immortalizing oral traditions through his research and poetry.

Challenges and struggles

The Banyarwanda in Uganda have faced many challenges and struggles in their quest for identity and rights. The first challenge was the colonial policy of divide and rule, which created artificial boundaries and ethnic divisions among the people of the region. The British colonial authorities favored the Tutsi over the Hutu and the Twa and granted them privileges and positions in the administration and the army. The Belgians, who controlled Rwanda and Burundi, did the opposite and supported the Hutu over the Tutsi and the Twa, encouraging them to revolt against the Tutsi monarchy. The colonial powers also introduced identity cards that classified people according to their ethnicity, which further entrenched ethnic differences and tensions .

The second challenge was post-colonial politics and conflicts, which resulted in violence and displacement of the Banyarwanda in Uganda and the neighboring countries. The independence of Uganda in 1962 was followed by a series of coups and civil wars, which destabilized the country and its institutions. The Banyarwanda in Uganda were often targeted and persecuted by the different regimes and factions, who accused them of being loyal to Rwanda or of being rebels and spies. The Banyarwanda in Uganda also suffered from the spillover effects of the conflicts in Rwanda and Burundi, which erupted in the 1960s and 1990s and led to the massacres and genocides of the Tutsi and the moderate Hutu by the extremist Hutu. The Banyarwanda in Uganda either fled from the violence or joined the armed groups that fought against the perpetrators, such as the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), which eventually took over Rwanda in 1994 and ended the genocide .

The third challenge was the legal and constitutional status of the Banyarwanda in Uganda, which has been ambiguous and controversial. The Banyarwanda in Uganda have been recognized as one of the indigenous tribes of Uganda in the 1995 constitution, which was amended in 2005. However, the implementation of this recognition has been hampered by the lack of a clear definition and criteria for who is a Banyarwanda and who is not. The Banyarwanda in Uganda have also faced discrimination and exclusion from the national identity cards and passports, which are required for accessing basic services and rights in the country. The Banyarwanda in Uganda have also been denied representation and participation in local and national politics and governance, which has marginalized them from the decision-making and development processes .

Renaming the tribe

In response to these challenges and struggles, the Banyarwanda in Uganda have launched a campaign to rename their tribe "Abavandimwe,” which means brethren in Kinyarwanda. The campaign is led by the Council of Abavandimwe, a group of Banyarwanda leaders and activists who have been advocating for the rights and interests of the Banyarwanda in Uganda. The campaign aims to change the perception and attitude of Ugandan society and government towards the Banyarwanda and to foster a sense of belonging and unity among the Banyarwanda themselves.

The campaign argues that the name “Banyarwanda” is misleading and confusing, as it links the Banyarwanda in Uganda with the neighboring country of Rwanda and implies that they are foreigners or immigrants rather than citizens or natives of Uganda. The campaign also contends that the name “Banyarwanda” is divisive and polarizing, as it reflects the ethnic divisions and conflicts that have plagued the region and prevents the Banyarwanda from integrating and harmonizing with the other tribes of Uganda. The campaign proposes that the name “Abavandimwe” is more appropriate and inclusive, as it emphasizes the bond of brethren, transcends ethnic and national boundaries, and celebrates the diversity and solidarity of the Banyarwanda .

The campaign has been conducting consultations and sensitizations among the Banyarwanda in Uganda and has received positive feedback and support from many of them. The campaign has also been engaging with the Ugandan authorities and stakeholders and has submitted a petition to the parliament, requesting the amendment of the constitution and the laws to reflect the new name of the tribe. The campaign hopes that the renaming of the tribe will be a step towards the recognition and acceptance of the Banyarwanda in Uganda and will pave the way for their social and economic empowerment and development .

Conclusion

The Banyarwanda in Uganda are a Bantu ethnolinguistic group that has a long and complex history and culture in the African Great Lakes region. They have faced many challenges and struggles in their quest for identity and rights in Uganda, where they are often mistaken or categorized as foreigners and discriminated against and excluded from the economy and public service of the country.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0