Ik (Teuso): A Tribe on the Brink of Extinction

The Ik, generally peaceful people, are frequently invaded by neighboring tribes.

Imagine living in a remote mountain range, surrounded by hostile neighbors and wildlife, with little access to education, health care, or political representation. Imagine being one of the last members of your tribe, whose culture and language are threatened by assimilation and neglect. Imagine being an Ethur Ik, or Teuso, a tribe in Uganda that is considered endangered by some.

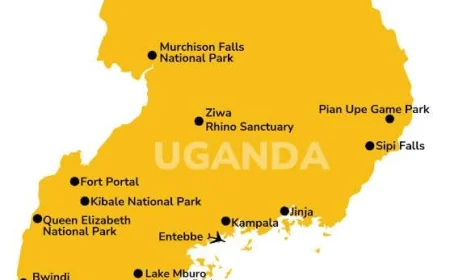

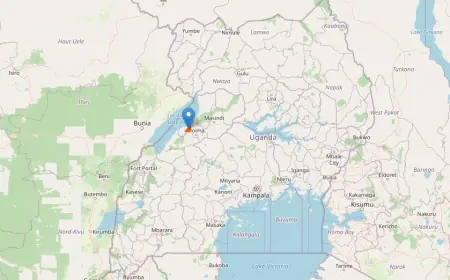

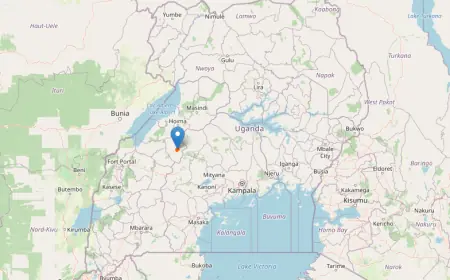

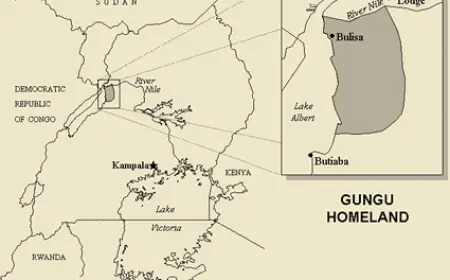

The Ethur Ik are an ethnic group or tribe native to northeastern Uganda, near the Kenyan border. They live in the area surrounding Mount Morungole in the Kaabong district, next to the more populous Karamojong and Turkana peoples. Their estimated population is between 10,000 and 15,000.

History and Origins

The word Ik means “head”; they are traditionally believed by locals to have been some of the region's earliest settlers from Kenya. They are part of the Kuliak sub-group of Nilo-Saharan languages, which also includes the So and Nyangia tribes.

The Ethur Ik have a controversial history, as they have been the subject of anthropological debates and media portrayals. In 1972, they were the focus of Colin Turnbull’s book The Mountain People, which described them as traditionally nomadic hunter-gatherers who had turned to farming due to external pressures. Turnbull described them as a society that had lost its moral values and social cohesion, resorting to selfishness, violence, and child abandonment.

However, Turnbull’s claims have been challenged by other researchers, such as Bernd Heine, who conducted linguistic and ethnographic studies of the Ethur Ik in the 1980s. Heine found that the Ethur Ik had a rich and complex culture, with rituals, festivals, clans, and elders. He also argued that they were historical farmers who hunted and foraged supplementarily and that their social problems were caused by poverty, famine, and insecurity, not by cultural degeneration.

Culture and Traditions

The Ethur Ik are divided into patrilineal clans, of which Heine noted twelve. Clans are led by the J’akama Awae, an inherited position. Marriages between members of different clans occur; in these cases, women retain their original clan identity, while their children are born members of the father’s clan. Clans live in small, walled villages known as odoks or asaks.

The Ethur Ik have several rituals that mark important stages of life. The most significant ones are ipéyé-és and tasapet. Both are considered rites of passage and are practiced by only men: ipéyé-és marks the beginning of manhood, and tasapet the initiation to elderhood. In ipéyé-és, young men must slaughter a male goat instantaneously, using a spear that may not penetrate the other side of the goat’s body. In Tasapet, older men must perform a series of tasks, such as climbing a mountain, carrying a heavy load, and reciting oral traditions.

The Ethur Ik also celebrate itówé-és (“blessing the seeds”), a three day festival that marks the beginning of the agricultural year. During this festival, they perform dances, songs, prayers, and sacrifices to ensure a good harvest. They also exchange seeds and gifts with other clans and tribes.

The Ethur Ik are predominantly Christian, having been converted by missionaries in the 20th century. However, they also retain some of their traditional beliefs and practices, such as worshipping ancestral spirits and natural forces.

Rituals

There are rituals in Ik culture, the most important of which are ipéyé-és and tasapet. Both are regarded as rites of passage and are solely practiced by men: ipéyé-és represents the start of manhood, while tasapet represents the transition to elderhood. In ipéyé-és, young males must slay a male goat in an instant with a spear that may not enter the other side of the goat's body. Tasapet may not be accomplished by a guy until all of his older brothers have done so. After this, his hair will be shaved, and he will be brought to live in the bush for a month while butchering a bull. Men who have finished tasapet are regarded as the most important members of the Ik: no decisions can be made without their approval, and they are entitled to respect from those younger. As of 1985, this custom could be endangered due to the high cost of obtaining livestock from neighboring communities.

Marriage

Marriage is usually planned between families, and engagements can be made when the bride is as young as seven or 10 years old. The groom's family is expected to pay a bride price, and the groom is required to work for the bride's family for a set amount of time. The first marriage ceremony, known as tsan-es, involves the engaged being rubbed with oil. The groom next throws a spear at a tree, putting his hunting prowess to the test. Following that, the bride is required to cook and conduct domestic work for the groom's family while they assess her capacity to integrate with them. In the second ceremony, the groom's family brings the bride cows and grain. They are greeted with beer, and any outstanding issues between the two families are addressed. Following a few days of festivities, the bride returns with the groom's family. In subsequent ceremonies, the groom is supposed to serve food or drink to other clan members in order to help the newlyweds integrate into society.

Holidays

Heine mentioned three main holidays in his report, the most important being itówé-és, or "blessing of the seeds." The holiday is observed for three days, usually in January, and symbolizes the start of the agricultural season. On the first day of the festival, a sacred tree is planted, and people bring their seeds to be blessed beneath it, which includes dancing around the tree. Beer is brewed, and the next morning, elders sample it before drinking it. No one may drink unless the senior members of the tribe have done so before. The second most important Ik celebration is Dzíber-ika mεs, often known as "beer of the axes." Individual families brew beer and bring it to the di, the elders' meeting spot, along with their agricultural instruments. The beer is sipped and then sprinkled on the tools to bless them. It is typically commemorated in November or December. In August, Inúmúm-έs, or "opening the harvest," is celebrated. Harvested grains are cooked together and eaten by the men at the di.

Generosity

Turnbull's ethnography from 1972 defined the Ik as "unfriendly, uncharitable, inhospitable, and generally mean as any people can be." Other newspapers, like The New York Times, echoed this impression of the Ik, describing it as a "haunting flower of evil." However, Catherine Townsend of Baylor University issued a paper in the twenty-first century that completely refuted these claims. Using the Dictator Game, a standard anthropological test, the Ik showed generosity comparable to most other cultures. The Ik believe in natural spirits known as kíʝáwika, who reward charity. According to Townsend, Turnbull's image of the Ik may have been influenced by the group's current starvation.

The Ik, generally peaceful people, are frequently invaded by neighboring tribes. They have a traditional dance in which they rehearse responding to an attack, with men defending the community and women guiding children to hidden locations and caring for the wounded.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0