Bakonzo (Bakonjo): The Indigenous People of the Rwenzori Mountains

The Bakonzo, Konjo (pl. Bakonzo, sing. Mukonzo), or Konzo are Bantu-speaking people who have lived on the slopes and valleys of the Rwenzori for centuries.

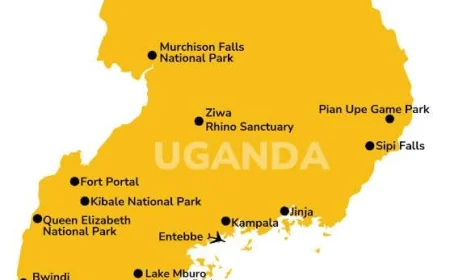

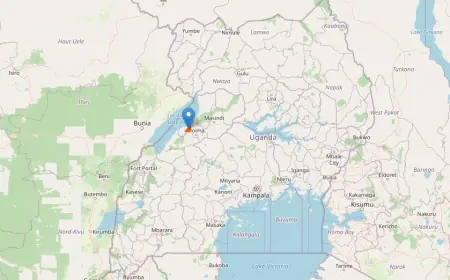

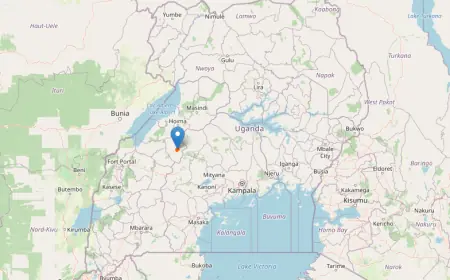

The Rwenzori Mountains, also known as the Mountains of the Moon, are a majestic range of snow-capped peaks and glaciers that straddle the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They are home to a rich biodiversity of plants and animals, as well as a unique cultural group: the Bakonzo.

The Bakonzo, Konjo (pl. Bakonzo, sing. Mukonzo), or Konzo are Bantu-speaking people who have lived on the slopes and valleys of the Rwenzori for centuries. They are estimated to number about 850,000 in both countries, with the majority residing in Uganda. They have a distinctive identity, history, and way of life that sets them apart from their neighboring tribes.

Origin and Migration of the Bakonzo

The origin of the Bakonzo is shrouded in mystery and legend. Some sources claim that they once lived on Mount Elgon in eastern Uganda and migrated westward with the Kintu migrations, a mythical event that is said to have brought the first Bantu settlers to the region. However, instead of settling in Buganda, the Bakonzo continued their journey until they reached the Rwenzori Mountains, which had a similar climate and terrain to their previous home.

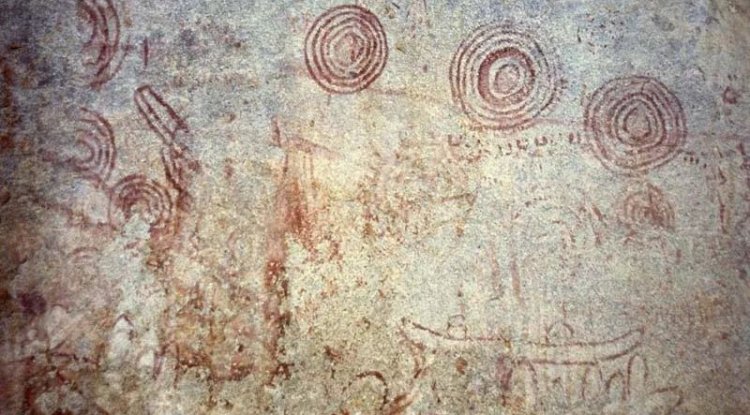

Other sources suggest that the Bakonzo have no foreign place of origin and have always inhabited the Rwenzori Mountains since time immemorial. They believe that they are the descendants of the original creation by the supreme god Nyamuhanga, who fashioned them from clay and breathed life into them. They also claim to have a special connection with the mountains, which they regard as sacred and the source of their livelihood.

Regardless of their exact origin, the Bakonzo have developed a strong attachment and adaptation to the Rwenzori Mountains over the years. They have learned to cope with the harsh and variable conditions of the high-altitude environment, such as cold, rain, fog, and landslides. They have also cultivated a variety of crops and animals that suit their ecological niche, such as yams, beans, sweet potatoes, peanuts, soy beans, potatoes, rice, wheat, cassava, coffee, bananas, cotton, goats, sheep, and poultry.

Culture and Traditions of the Bakonzo

The Bakonzo have a rich and diverse culture that reflects their history, beliefs, and values. They have a complex social organization that is based on clans, totems, and age groups. They have 14 clans, each with its own totem, which is usually an animal or a plant that symbolizes the clan’s origin and characteristics. The clans are exogamous, meaning that one cannot marry within one’s own clan. The totems are also used as a form of greeting and respect among the Bakonzo.

Initiation among the Bakonjo

Initiation ceremonies were a crucial aspect of Bakonjo culture, sharing similarities with the Bamba tribe. These rites marked the transition from childhood to adulthood for male initiates, typically involving circumcision and jointly performed by both the Bakonjo and Bamba communities. The initiation process, occurring every fifteen to seventeen years, encompassed all male children from the age of three. Uncircumcised men were not considered true Bakonzo, reflecting the cultural significance of this practice. While the Bagisu celebrated circumcision annually, the Bakonzo regarded it as an integral part of life rather than a ceremonial event. Historically, ritual circumcisions were centralized in Bundibugyo until 1964, when the last one occurred, performed by Bamba tribesmen. Today, circumcision can be performed by anyone with expertise, regardless of age, highlighting its enduring importance within Bakonjo society.

Marriage traditions of the Bakonjo

Marriage within the Bakonjo and Bamba communities held significant social importance, often arranged from a young age. Families typically initiate marriage arrangements on the day of the boy's initiation ceremony, with social recognition contingent upon the settlement of bride wealth obligations, usually paid in goats, along with a digging stick and animal skin, later replaced by a hoe and blanket in modern times. Divorce was uncommon, but if it occurred, the bride's wealth was returned. Unmarried girls were expected to be virgins, with severe consequences for premarital pregnancy.

Traditionally, when a girl was born, fathers with sons would bring gifts to her parents, signaling interest in potential marriage alliances. These gifts played a crucial role in the parents' decision-making process regarding their daughter's future spouse, often indicating the financial status and reputation of the suitor's family. Close friendships between families with unmarried sons could also influence marriage arrangements, strengthening social bonds.

Once a family was chosen, the girl's parents accepted gifts exclusively from them, signifying the acceptance of the suitor's family as potential in-laws. The girl would later be sent to live with her future in-laws around the age of seven, with the bride's price, Omukagha, paid during a small ceremony attended by elders from the boy's family. However, this arrangement did not imply marriage at such a young age; rather, the couple began to interact more closely around the girl's twelfth year. At this point, she would typically reside with her future husband's family until marriage, a tradition rooted in the belief that children of that age were mature enough to understand their marital responsibilities.

Bakonzo Child birth rituals

Following childbirth, cultural rituals dictated that a woman refrain from sleeping on her marital bed until the cessation of bleeding. However, when twins were born, known as Abahasa, the mother, or Nyabahasa, was required to engage in a ceremony called Olhuhasa before returning to her husband's bed. The announcement of her readiness signaled the commencement of preparations for the event, including the construction of a hut in the husband's compound.

Anticipation mounted as the Salongo or Isebahasa spread news of the impending Olhuhasa among social circles. Amidst a large gathering, Nyabahasa would engage in sexual intercourse with her husband's oldest nephew inside the designated hut. Failure to complete the ritual was believed to endanger the twins' lives, leading to subsequent attempts by other nephews until success was achieved.

The sexual encounter between the nephew and his aunt was strictly confined to the ritual, and any excessive crying by the Bahasa infants was viewed as an indication of potential parental infidelity. This belief underscored the idea that the twins' parents were exempt from societal norms.

The decline of such traditions, including Olhuhasa, can be attributed to factors like HIV awareness, education, and modernization. Nevertheless, remnants of these practices persist, particularly among the Bakonzo, renowned for their adherence to cultural traditions.

History and Politics of the Bakonzo

The Bakonzo have a long and turbulent history that has shaped their political and social status in the region. They have faced various forms of oppression, resistance, and rebellion from both external and internal forces.

The Bakonzo were initially independent and autonomous, but they came under the influence and dominance of the Toro Kingdom, a centralized monarchy that was established by the Batooro in the 18th century. The Toro Kingdom imposed taxes, tribute, and labor on the Bakonzo, who resented their subjugation and exploitation .

The situation worsened during the colonial era, when the British administration recognized and reinforced the authority of the Toro Kingdom over the Bakonzo. The Bakonzo were denied representation, education, and development opportunities by the colonial and Toro regimes. They were also subjected to discrimination, violence, and land alienation by the Batooro and other immigrants who settled on their ancestral lands .

The Bakonzo responded to their oppression by organizing a resistance movement known as the Rwenzururu, which literally means “the land of snow." The Rwenzururu movement started as a cultural and self-defense association in the 1950s, but it later evolved into a political and military force that fought for the independence and recognition of the Bakonzo and their allies, the Bamba, from the Toro Kingdom and the central government .

The Rwenzururu movement reached its peak in the mid-1960s and early 1980s, when it engaged in armed clashes with the Toro and government forces, resulting in hundreds of casualties and thousands of refugees. The movement also declared the establishment of the Rwenzururu Kingdom, a separate entity that claimed sovereignty over the Rwenzori region and its people .

The Rwenzururu movement was eventually suppressed and pacified by the government, which offered amnesty, integration, and dialogue to the rebels. In 2008, the government officially recognized the Rwenzururu Kingdom as Uganda’s first kingdom, shared by two tribes, the Bakonzo and the Bamba. The leader of the Rwenzururu movement, Charles Mumbere, was crowned the Omusinga (king) of the Rwenzururu Kingdom .

However, the recognition of the Rwenzururu Kingdom did not end the conflicts and tensions in the region. Since 2014, there have been renewed outbreaks of violence and instability, fueled by secessionist ambitions, ethnic rivalries, land disputes, and political grievances. The Rwenzururu Kingdom has been accused of harboring and supporting armed groups that seek to create a separate state, known as the Yiira Republic, that would encompass parts of Uganda and Congo. The government has responded by deploying security forces and arresting and prosecuting the Rwenzururu leaders and supporters .

The Bakonzo, therefore, remain a marginalized and vulnerable group that faces multiple challenges and threats to their survival and dignity. They are caught in a cycle of poverty, underdevelopment, and conflict that hinders their social and economic progress. They are also at risk of losing their cultural and environmental heritage, as the Rwenzori Mountains are threatened by climate change, deforestation, and mining .

Conclusion

The Bakonzo are a remarkable people who have a unique and fascinating culture, history, and identity. They are the indigenous people of the Rwenzori Mountains, a natural wonder that they revere and depend on. They have endured and resisted various forms of oppression and domination and have asserted their autonomy and recognition.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

1

Wow

1